This blog post is a detailed summary of my recent keynote at ACM RecSys 2025 in Prague. You can watch the full video here.

I’ve been involved with RecSys for a long time. This keynote was my 11th. I attended the first six, so I was there in the early days—and I’ve watched the field repeatedly reinvent itself.

One of my favorite personal “RecSys origin stories” is that when I transitioned from academia to industry, I found my job through this community. In Barcelona 2010, I started conversations that led me to Netflix, and eventually to many other things. I look around today and see people who have been interns with me and then followed similar paths. That’s part of what makes this community special: it’s a rare intersection of industry + academia + practitioners, with a shared obsession not only for algorithms, but for product, users, and psychology.

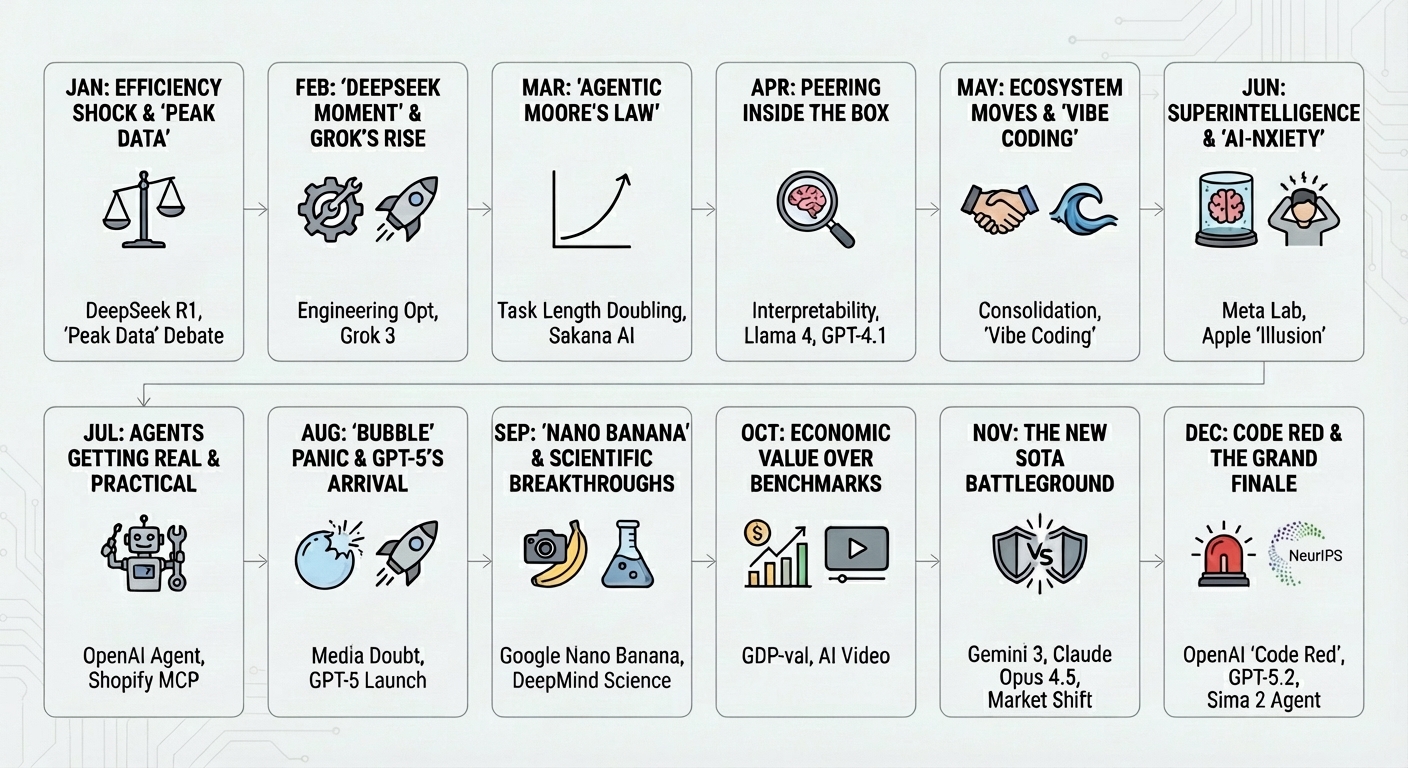

This talk had three parts:

- How we got here (history, with some personal bias)

- Recommending in the age of GenAI (the present)

- What’s coming next (where I think we’re heading)

Part I — How We Got Here

MovieLens v0, 1997, and the “field becomes a field”

Early in the talk I put up a screenshot that not everyone recognized: MovieLens v0 (published around 1997). For me, that interface is more than nostalgia. It’s a marker that a set of ideas turned into a recognizable field—built by Joe Konstan, the late John Riedl, and the rest of the University of Minnesota team.

It’s also why the first RecSys conference was held in Minneapolis—and why going back there feels like a loop closing and reopening.

AI history, intertwined with RecSys history

I deliberately intertwined recommender systems history with the history of AI, because the two have been co-evolving for decades:

- 1950s: “Artificial Intelligence” is coined at Dartmouth; Rosenblatt publishes the perceptron paper.

- 1969 → 1970s: Minsky’s critique leads to the first AI winter.

- 1980s: expert systems become fashionable again; then people rediscover their brittleness and scaling limits.

- 1987–1993: another AI winter.

- 1997: MovieLens, early RS papers.

- 2006–2009: Netflix Prize (we’ll spend time here).

- 2007: RecSys conference starts (on the heels of Netflix Prize energy).

- 2011–2016: deep learning momentum hits recommender systems (YouTube DL recommender paper is a major moment).

- 2018: Transformers (“Attention is All You Need”).

This timeline matters because it shows a pattern: RS progresses when model capability, data availability, and product surfaces line up—and stalls (or misleads us) when we optimize the wrong abstractions.

Netflix Prize: a turning point, and a lesson about proxies

The Netflix Prize (2006–2009) was pre-Kaggle, pre-everything we now take for granted. It was a massive public experiment. The goal was framed as “better recommendations,” but the proxy objective was explicit: improve RMSE on rating prediction by 10%, win $1M.

The winning solution was instructive:

- It was an ensemble (as usual).

- It combined 104 models using a neural network.

- The “main” approaches were a matrix factorization / SVD variant and restricted Boltzmann machines (a neural net).

Then came the part I think many people remember less clearly: we took the work back to Netflix and asked, “Can we productionize it?” The answer was: not as-is.

- 104 models didn’t scale well, was too slow, too complicated.

- More importantly: while we were doing that translation work, we realized something deeper: the objective itself (RMSE on ratings) was not the right question.

We did productionize SVD and RBMs—they were the first ML algorithms that went into Netflix’s product. But the Netflix Prize still taught a durable lesson: You can win the benchmark and still lose the product. Or, more precisely: your offline proxy can be “correct” and still be wrong.

From “algorithms” to “machine learning” to “AI”

Back then, we didn’t even say “machine learning.” We said algorithms. My team at Netflix was literally called Algorithms Engineering. Over time, the naming shifted: algorithms → ML → AI. That branding shift wasn’t just marketing; it reflected real changes in how systems were built and what people expected of them.

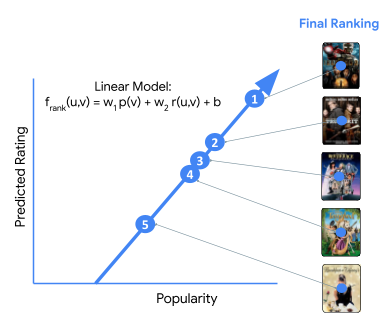

I used a simple example to make this concrete: the most basic personalized recommender you can build—almost comically basic by today’s standards.

- Two features: Popularity, Predicted rating

- Two parameters: w1 and w2

- A linear model

The task: learn w1 and w2 from user behavior data. It’s a useful toy model because it captures a core truth: the system is mostly the same loop, regardless of complexity: choose features, choose model family, estimate parameters from data, measure whether it helped users.

We used to “advance ML” by adding more features and making models more complex. Feature engineering mattered and it required domain knowledge.

I gave a Quora example that still resonates with me: ranking answers for a question. It sounds obvious until you try to formalize it. We had to talk to editors and journalists about what “good” meant. They said: truthful, reusable, well-formatted, not too long, the right length. That became features. And then those features got learned.

That was “old-school” ML—though, honestly, we still do versions of it today.

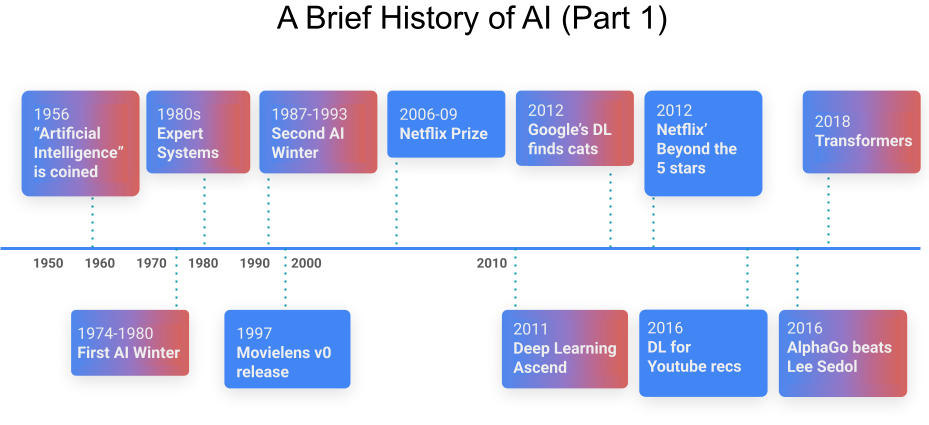

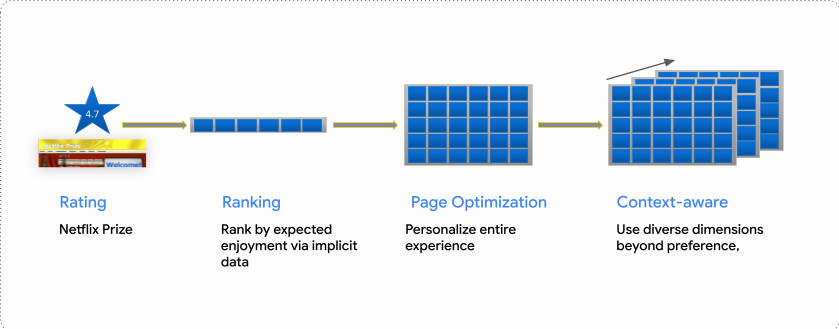

The recommender problem evolved: rating → ranking → page → context

Another key arc: the problem definition evolved.

- Point-wise prediction: predict a rating (Netflix Prize era)

- Ranking: learn to order items

- Page optimization: optimize a full surface (rows, shelves, competing modules)

- Context-aware: device, time of day, location, intent—more dimensions

This wasn’t an academic shift. It was driven by the reality that a product isn’t a “list.” It’s an environment. At this point in the talk I referenced two of my own prior contributions:

- The Netflix work on “Beyond the five stars”, emphasizing why implicit feedback often beats explicit ratings for real-world optimization.

- The “Multiverse recommendation” work (published at RecSys in Barcelona 2010), which became my most cited RecSys paper—explicitly leaning into context-aware recommendation.

Deep learning in recommender systems: two-tower (and the promise of representation learning)

Then came deep learning’s major wave in RecSys—roughly 2011 onward—culminating in the “deep learning for YouTube recommendations” moment that hit this community hard.

To ground it, I showed the classic two-tower model:

- user embedding tower

- item embedding tower

- dot product to score similarity / relevance

It’s not the best model, but it’s the right mental starting point. Even in 2014 we were already experimenting with distributed neural nets in production contexts. And by 2016–2017, I was explicitly framing this as “the recommender problem revisited,” because deep learning forced us to revisit assumptions about features, modeling capacity, and system architecture.

(Geeky rabbit hole — Deep learning “replaced feature engineering”… but RecSys had already been blending paradigms)

Deep learning’s promise was: “stop hand-crafting features; the model learns representations.” But there’s a subtle connection to how recommenders already worked. Even matrix factorization is, in a sense, a hybrid of:

- unsupervised structure learning (dimensionality reduction, latent factors)

- supervised signal (ratings, implicit feedback)

We were already combining unsupervised and supervised approaches in clustering and latent-factor methods. Deep learning didn’t invent the idea; it industrialized it and scaled it—and then moved us more explicitly into self-supervision.

I tied this to the “multi-layer cake” framing of modern ML:

- self-supervised pretraining

- supervised fine-tuning

- reinforcement learning / alignment as the “icing”

This “layered training” view is something I’ve written about in the context of modern LLMs—especially the idea that “token prediction” alone undersells what post-pretraining adds.

It’s not only about algorithms

At this point I paused and emphasized a point that’s easy to say and hard to operationalize: In recommender systems, the algorithm is rarely the whole system.

I summarized the “non-algorithm” pillars as:

- UX / design

- Domain knowledge

- Evaluation metrics

UX / design: I showed an early Netflix interface where the page was packed with explanations: predicted rating, “because you watched X”, actors, director, etc. Those explanations—and the way we presented choices—often mattered as much as the model. This also connects to why Netflix ultimately moved from stars to thumbs: the UX and the feedback mechanism are part of the learning loop.

Domain knowledge: Even with deep learning, you still need domain knowledge—especially in constrained domains like healthcare. Constraints aren’t optional; they’re foundational.

Evaluation metrics: You need offline and online evaluation. You must iterate fast with offline proxies, validate with online experiments, and connect short-term metrics to long-term satisfaction/retention. I cited a memorable result from a YouTube team study: long-term satisfaction was causally linked not merely to “more consumption,” but to diversity of content consumed. If you get people to consume a more diverse set of content, they tend to be more satisfied in the long run. That finding matters because it’s a reminder that “maximize clicks” is not the same thing as “maximize sustained satisfaction.”

Part II — Recommending in the age of GenAI

Bill Gates wrote, “the age of AI has begun.” I used that line to mark the present moment—because Transformers, LLMs, and GenAI changed both the research conversation and the product conversation.

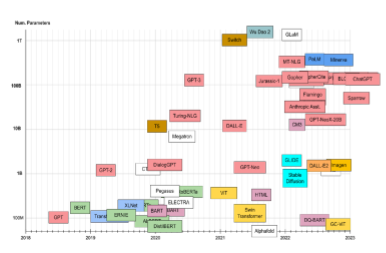

Two parameters → trillions of parameters

I showed a plot: transformer research families over time, parameter counts rising from ~100M to beyond a trillion. It’s worth repeating the contrast because it captures the discontinuity: earlier I showed a recommender with two parameters (popularity weight and predicted-rating weight). Now we’re in a world where models have trillions of parameters. All of those parameters still get learned from data—just through a very different pipeline.

Even “research impact” got weird

I mentioned how my citations changed dramatically in 2024–2025 because I posted three arXiv works: an LLM survey, a prompt design/engineering publication, and my transformer catalog. They weren’t even peer-reviewed in the traditional sense—yet the field’s attention was so concentrated that the impact was immediate. That’s not a moral argument; it’s an observation about attention allocation in the current research ecosystem.

How GenAI is already changing recommender systems

I gave three examples (largely from Google) to illustrate trends:

- LLMs for understanding preferences

- Generative retrieval

- Transformers applied to content-heavy recommendation contexts (e.g., music)

Then I returned again to the earlier triad (UX, domain knowledge, evaluation) and argued they still matter—but differently now:

- UX and AI are now intertwined; sometimes the UX is the AI (chatbot-style discovery).

- Pretrained foundation models carry a lot of domain knowledge out of the box—but domain expertise still matters for constraints and evaluation.

- Evaluation is arguably more important now; measuring GenAI is hard, and feedback loops are subtle.

Demo 1: “basic LLM” recommendation from a handful of shows

I demonstrated a simple prompt in Gemini: I gave it four Netflix shows I liked and asked for recommendations. What mattered wasn’t only the recommendation list—it was the “thinking trace” the model surfaced: identify attributes, extract themes, find common threads, craft categories, then produce options. And it worked. The model recommended:

- Ozark (which I’d seen and liked)

- Mindhunter (which I hadn’t seen)

- Narcos (which I’d seen and liked) Also: it was different each time—both the blessing and the curse of generative systems.

Demo 2: zero-history preference elicitation in five questions

Then I made it more interesting: “assume you know nothing about me—ask me five yes/no questions and recommend five music artists I’ll like.” Again, the point wasn’t just the output. The model:

- designed a question flow

- implicitly built a decision tree

- updated a “user profile” after each answer

With five questions, it recommended: Tool, King Crimson, Animals as Leaders, Russian Circles, and Karnivool. I noted that some picks were a bit off for my taste—likely influenced by how I answered the “harsh vocals” question. But the more important observation remained: from a blank sheet, the system elicited preferences and produced plausible recommendations.

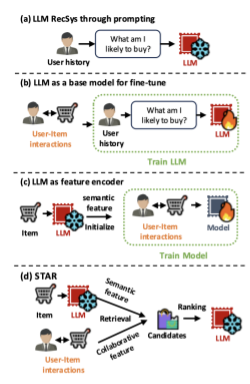

A taxonomy of how LLMs enter RecSys

I referenced a diagram from the STAR paper that classifies approaches (see below):

- pure prompting (like my demos)

- prompting with user history (user–item interactions)

- using LLMs to create semantic features/IDs/embeddings combined with collaborative signals

- two-LLM architectures: one for semantic features + CF, another LLM for final ranking The meta-point: “using LLMs” isn’t a single technique; it’s a design space.

Part III — What’s next

I started this section with a screenshot from a startup called Fable: “Netflix for generative content.” The proposition is an extreme endpoint of personalization: not only recommending content but generating content, on the fly, personalized to each user. That’s “the last step” of personalization in one direction.

Then I returned again—intentionally—to the product triad:

- UX design (especially in multimodal / agentic worlds)

- Domain knowledge + deep, continuous user knowledge

- Evaluation (now vastly harder)

Demo 3: a recommendation agent (Localify)

I showed an agent built with Google AgentSpace. I called it “Localify.” Its job was simple: ask the user about tastes, search local events, and help find tickets. In the live demo, the agent didn’t ask the preference questions because it already “knew” my earlier answers (I had tested it). Based on what it remembered—rock, jazz, music, cinema—it recommended:

- an indie rock concert

- a jazz evening

- an independent drama film

Then it helped find a link for tickets. What I wanted to emphasize was how small the barrier has become:

- the agent prompt was basic

- I used “help me write” and the LLM improved the prompt

- it took minutes, not weeks

And if you want to make it more powerful, you can connect it to tools: calendar, email, enterprise systems, backend databases, …and even (dangerously) payment.

(AI digression — the moment you add tools, you import responsibility) In one of my posts, I put it bluntly: AI is great for organizing/analyzing data, but it doesn’t have “gut,” intuition, or accountability—and that’s precisely why human judgment remains central. That maps directly to agents: the moment an agent can act, UX design and safety constraints stop being secondary concerns.

Agents that browse the web and recommend

I then showed a more advanced agent concept (Project Mariner): it can browse the web on your behalf—scroll, click, match opportunities to your resume, and execute a multi-step flow. The only additional capability (conceptually) is huge: delegated navigation in human UIs.

World models (Genie 3) and “generated reality”

I showed a clip of “Genie 3,” positioning it as a frontier: not just generating text or images, but generating interactive worlds, with real-time reactivity, “world memory” (actions persist), and promptable events. This opens a window to a future where “personalized media” is not just personalized content—it’s personalized environments.

Deep, continuous user knowledge: the personalization paradox

LLMs have huge world knowledge; what’s still hard is injecting knowledge about you—accurately, safely, continuously. I showed a Gemini direction: more persistent memory so you don’t need to repeat “I like jazz and indie cinema” every time. That’s the personalization paradox: the model knows the world, it still struggles to know you (and to update that knowledge responsibly).

Research directions I highlighted

I ended with a set of recent papers (three examples) illustrating trends:

- aligning LLM-powered systems to user feedback (and novelty)

- serendipity / novelty with multimodal signals

- hybrid strategies that combine fine-tuning (infrequent) with RAG (more frequent) to keep user modeling fresh without constantly retraining

Conclusion: a journey from clicks to conversations

I closed with a framing I’d encourage you to keep in mind as you design systems in 2026 and beyond: We’ve revisited the recommender problem multiple times. We started with predicting stars, then clicks. We’re shifting into conversations, and now agents—long-running, tool-using systems that discover on our behalf.

My current bets are:

- Agents are the future of discovery. They’ll search, filter, and propose options in the background, then surface novel things for us to engage with.

- Personalization will remain the hard part. World knowledge scales. “User knowledge” is messy, dynamic, private, and consequential. Evaluation is the new frontier. Especially for long-running, multi-step systems where value accrues over time and failure modes are subtle.

- The ultimate prize might be “media of one.” Content not only discovered for you—but created for you, on the fly, personalized to what you want right now.

And, because this is RecSys: karaoke remains a constant—and apparently so do 7am runs.

Q&A moments worth carrying forward

A few audience questions surfaced important tensions:

Recommend from catalog vs generate unique items? The cultural value of shared artifacts matters. If everyone gets a different show, what happens to shared conversation? My instinct: we’ll find hybrid dynamics—personalized creation plus social sharing (you can “send” your generated show).

Will users really have long conversations vs passive feeds? Different modes will coexist. There are “brain-dead scroll” moments and “high-ROI search” moments (finding the next book vs watching a 30-second clip). The adoption of chat products is a strong counterexample to the idea that people never want conversational interfaces.

If agents consume content, what incentives remain for creators? No clean answer yet. But historically, new creation tools tend to democratize creation rather than end it—and we should proactively design ecosystems that keep human creativity rewarded and visible.

References

- Amatriain, X. (2025). Keynote at ACM RecSys 2025

- Konstan, J. A., et al. (1997). GroupLens: Applying collaborative filtering to Usenet news

- Koren, Y. (2009). The BellKor Solution to the Netflix Grand Prize

- Karatzoglou, A., Amatriain, X., Baltrunas, L., & Oliver, N. (2010). Multiverse Recommendation: N-dimensional Tensor Factorization for Context-aware Collaborative Filtering.

- Amatriain, X. & Basilico, J. (2012). Netflix Recommendations: Beyond the 5 stars.

- Le, Q. V., et al. (2012). Building high-level features using large scale unsupervised learning (The “Cat” paper).

- Covington, P., et al. (2016). Deep Neural Networks for YouTube Recommendations.

- Vaswani, A., et al. (2017). Attention Is All You Need.

- Amatriain, X. (2024). Transformer models: an introduction and catalog.

- Minaee, S., et al. (2024). Large Language Models: A Survey.

- Amatriain, X. (2024). Prompt Design and Engineering: Introduction and Advanced Methods.

- Lee, D., et al. (2024) STAR: A Simple Training-free Approach for Recommendations using Large Language Models

- Wang, J., et al (2025) User Feedback Alignment for LLM-powered Exploration in Large-scale Recommendation Systems

- Meng, C., et al. (2025) [Balancing Fine-tuning and RAG: A Hybrid Strategy for Dynamic LLM Recommendation Updates] (https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.20260)