In my previous post, I introduced the ten new lessons and described the first five. Let’s directly dive into the final 5.

6. the pains and gains of feature engineering

The main properties of a well-behaved machine learning feature are:

- Reusable

- Transformable

- Interpretable

- Reliable

What do these properties actually mean?

- Reusability: You should be able to reuse features in different models, applications, and teams

- Transformability: Besides directly reusing a feature, it should be easy to use a transformation of it (e.g. log(f), max(f), ∑ft over a time window…)

- Interpretability: In order to do any of the previous, you need to be able to understand the meaning of features and interpret their values.

- Reliability: It should be easy to monitor and detect bugs/issues in features

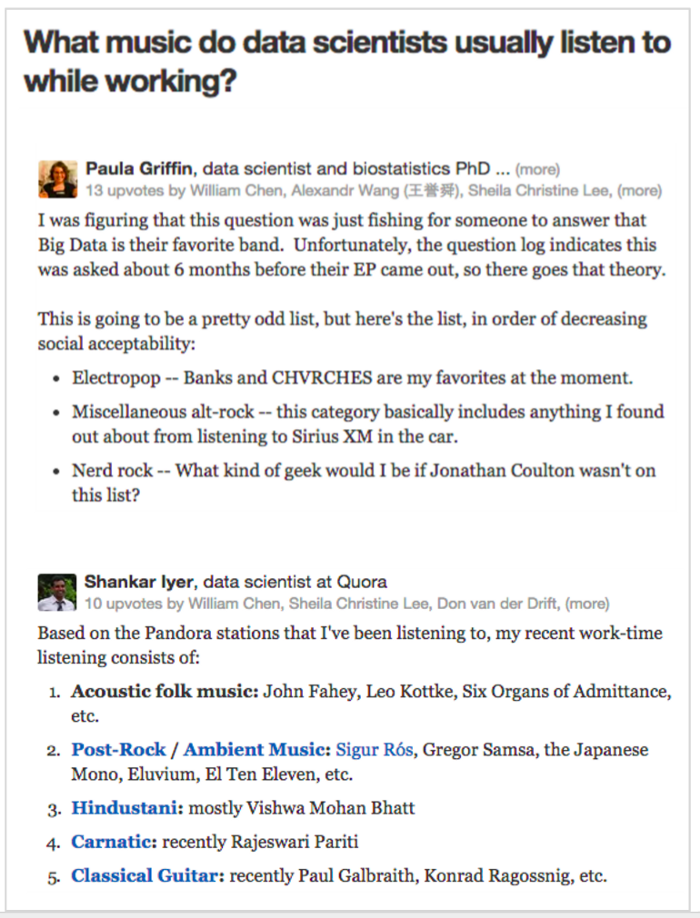

Let’s take a look at a practical example of feature engineering: Quora’s answer ranking. How can we figure out the features that are needed for developing a good model for answer ranking? First of all we need to understand how we define a “good” answer at Quora. Fortunately, we have a pretty detailed description in the Quora Answer Policies. In that description we will find qualifiers such as:

- truthful

- reusable

- provides explanation

- well formatted

- …

So, how can we translate those dimensions we care about into features that we can feed into our machine learning model? Well, the trick is to think what data we have in the product that relates to some of those properties. We can use features relating to the quality of the writing, interaction features such as upvotes or comments, and finally user features such as the expertise and trustworthiness of the user in the topic.

7. the two faces of your ML infrastructure

Whenever you develop any machine learning infrastructure, you need to keep in mind two different modes in which this infrastructure might be used:

- Mode 1: ML experimentation. In this mode we value flexibility, easiness of use, and reusability.

- Mode 2: ML production. In this mode we value all of the above plus performance & scalability

Ideally, we want both modes to be as similar as possible. So, how can we combine them?

One possible thought is to favor experimentation and only invest in productionizing once something shows results. This might mean, for example, to have machine learning researchers using R, and later ask engineers to implement things in production in their programming language of choice. Another extreme is to do the opposite: favor production and have researchers struggle to figure out how to run experiments. For example, you could decide to have highly optimized C++ code and have ML researchers experiment only through data available in logs or the database.

The reality is that both of the options above do not work. They are not efficient, they are wasteful in resources, and they end up leading to at least one of the modes not functioning correctly.

The trick is to implement intermediate solutions that can address needs on both modes. One example is to have ML researchers experiment on iPython Notebooks using Python tools (scikit-learn, Theano…), use the same tools in production whenever possible, and implement optimized versions only when needed. Another option is to implement abstraction layers on top of optimized implementations so they can be accessed from more friendly experimentation tools

8. why you should care about answering questions (about your model)

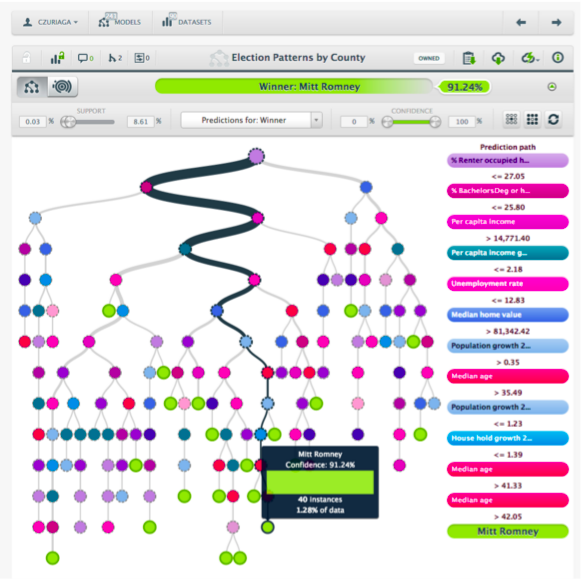

The value of a machine learning model is the value it brings to the product. Product owners and stakeholders in the process have expectations on how the product should behave and they want to verify them. It is important to be able to answer questions about why the model is doing something or why something failed. Model debuggability can actually bridge the gap between product design and machine learning algorithms.

I would argue that model debuggability is so important that it can end up determining, or at least influencing, the particular model to use, the features to rely on, or the tools used for the implementation.

As an example, we at Quora have a debug tool that allows us to analyze why we are seeing (or not seeing) a particular story in our homepage feed. This tool reports the score of not only individual stories but also of the features that refer to it. It also allows to compare different stories and understand what are the features that ended up deciding for one story to rank higher than the other. This has proved to be very useful in debugging issues and in making the product team and other stakeholders understand much better how the models behave and what matters or doesn’t.

9. you don’t need to distribute your ML algorithm

There is an industry trend recently where it seems that you should distribute your machine learning algorithm by default. If you are not doing so, it might mean that your data is not “big enough”, right? Well, here I am to tell you that no, that’s not the case. As a matter of fact, most of what people need to do with practical machine learning applications should fit into a single (multi-core) machine. Of course, there are notable exceptions to this such as if you are building large-scale Deep Artificial Neural Networks to identify cats. But, most of us are not in that business.

Of course, in order to fit things into a single machine, you need to understand other approaches. For example, you need to understand the benefits of (smart) data sampling, how to use offline processing schemes, or how to parallelize in a single machine. I actually talked about all these points in my [original 10 lessons](http://technocalifornia.blogspot.com/2014/12/ten-lessons-learned-from-building-real.html).

Furthermore, I think that approaches such as Hadoop and Spark, that offer “easy” access to distributed platforms by hiding most of the complexity are, in a way, dangerous. In particular, if you care about costs or latencies, not making them transparent or easy to understand is usually not a good idea.

Here is an interesting example from Quora that illustrates some of this. At some point we realized that we had a Spark implementation that was especially inefficient. It took 6 hours and 15 machines to run something that a back-of-the-envelope computation told us it should take much less. One of our engineers spent 4 days and looked into it by, for example, analyzing how the Spark scheduler unfolded the queries. The final C++ implementation runs now on a single machine and takes only 10 minutes to compute!

10. the untold story of data science and vs. ML engineering

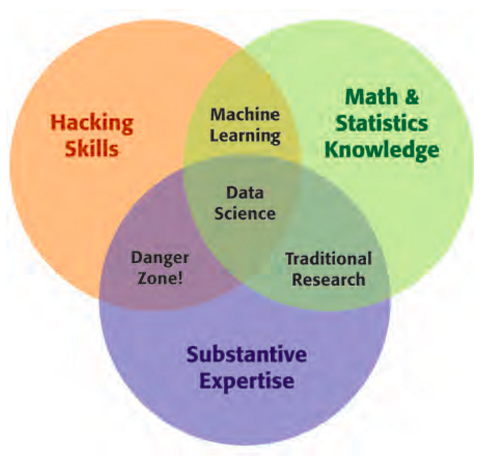

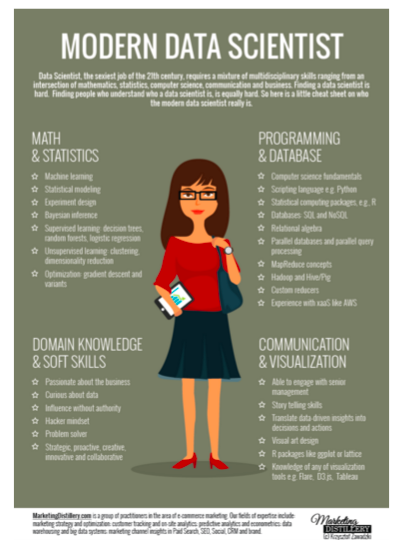

We have all heard and read answers to what a Data Scientist is. Most of them talk about how they need to combine math, software, and domain expertise.

A different question, is though, how do Data Science teams fit into an organization. Many companies have struggled, and are still struggling, with this. Most will agree that it is important to have strong data scientists who can generate value and knowledge from the data. However, regardless of what some may say, strong data scientists with solid engineering skills are unicorns, and finding them is not scalable. This often leads to situations where data scientists need to rely on engineers to bring things to production and, on the other hand, engineers don’t want to do this because they already have enough things on their plate to worry about productionizing somebody else’s ideas.

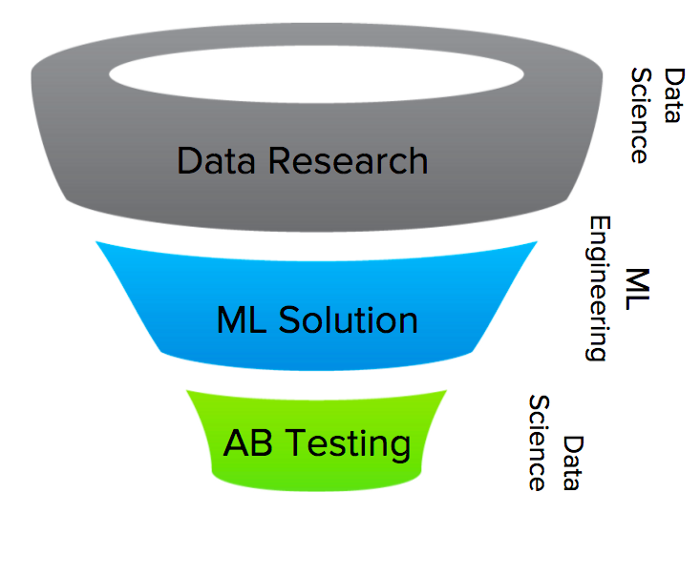

So, what is the solution? My recommendation is to think about the innovation funnel of a typical ML-related project. There are 3 distinct phases.

The first part of the funnel is where data research happens. This is where the team is looking at data and trying to understand what are the issues in order to formulate hypothesis. Are my users clicking more on the red button on Friday evening than in other days? Do users prefer newer content even if it is potentially lower quality? How can we tackle the exploration/exploitation tradeoff?

The second part of the funnel happens once the hypothesis has been formulated and we need to implement a machine learning solution. It involves choosing the model, doing feature engineering, and implementing the solution in production. It also includes not only the initial version of the solution, but future iterations to optimize and improve the current system.

The third and final part of the funnel focuses on running online experiments (AB tests) and analyzing the results. This way we can understand whether the solution that was implemented actually worked and confirmed our initial hypothesis.

It is important to note that these three phases do not need to take a long time and they should happen as quickly as possible in the context of a very iterative and agile process.

Based on many examples that I have seen, heard of, and experienced, my proposal is for Data Science to own and lead parts 1, and 3, and for engineering to own part 2. Having Data Science own part 1 and 3 in an iterative process also allows for faster iterations since results from experiments quickly flow back into improving our hypothesis. At Quora we do this by including both Data Scientists and Engineers in all projects and having them work close together while still allowing them to have clear understanding of their focus and area of ownership in the project. See William Chen’s answer to “What is the difference between a machine learning engineer and a data scientist at Quora?” for more details.

A final note is that in order for the machine learning engineering team to be effective, it may need to broaden its definition of what ML engineering means. Again, it is hard to find a large group of engineers that are both excellent at machine learning and software engineering (just as it is hard to build a soccer team by putting together 11 players that are all goal scorers). A good ML engineering team will include all the way from coding experts with high-level ML knowledge to ML gurus with acceptable software skills.

Conclusions

There are many non-obvious issues related to implementing practical machine learning solutions. Some of them are pretty different from what you will read in publications or even different from what is accepted to be the “common approach”. If I had to summarize these 10 new lessons in a couple of dimensions I would highlight the following:

- Make sure you teach your model what you want it to learn

- Ensembles and the combination of supervised/unsupervised techniques are key in many ML applications

- It is important to focus on feature engineering

- Be thoughtful about

- your ML infrastructure/tools

- organizing your teams

I hope these suggestions are helpful, but I will admit to at least some of them being controversial. I would love to hear more about different opinions and approaches in the comments.