It has been over 10 years since the Netflix Prize finished, and I was not expecting to write a blog post about it at this point. However, just in the past couple of weeks I have found myself talking about it extensively both in the context of a Twitter thread and discussion, as well as the shooting of an upcoming documentary series. Given that there seems to be continued interest as well as misunderstanding around the prize and its outcome, I thought it might be worth to “set the record straight” in a dedicated post.

TLDR; While I am often misquoted as having said that the Netflix Prize was not useful for Netflix, that is only true about the grand prize winning entry. Along the way, Netflix got far more than our money’s worth for the famous prize.

What was the Netflix Prize anyways?

Ten years ago, when I was leading Algorithms at Netflix, I would start my public presentations by asking the audience a couple of questions: “Who has heard about the Netflix Prize?” and “Who has participated in the Prize by submitting at least an entry?”. Virtually all hands would go up to the first question. Depending on the audience, more than half of the people would also raise their hands to the second. I would obviously not expect that to be the case anymore. However, I have recently been pretty surprised by how much folks in the ML/AI community remember or simply know about the contest. It is clear that it was somewhat of a historical event.

In 2006, Netflix launched a $1M competition to improve their recommendation algorithm. At that point I was a researcher in the field in a Barcelona lab, so I don’t have first-hand details of how and why the prize was decided internally and how it all got started (to be fair, I did get some of that insight once I joined the company 5 years later, but that part of the story is not very relevant anyways). For the thousands of participants around the world, the rules were quite simple: if you were able to beat the Netflix baseline (called Cinematch), you would win $1M. Not surprisingly, many researchers, students, and amateur mathematicians and computer scientists around the world jumped at the opportunity.

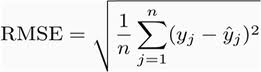

The mechanics of the contest were also quite simple: there was a training set consisting of around 100M data points including a user, a movie, a date, and a rating from 1 to 5 stars. There was a smaller public validation dataset called “probe” consisting of around 1.5M data points with no ratings. Finally, and very importantly, there were two test sets that hid ratings from participants. In order to test your algorithm you would submit your predictions to the so-called quiz test and you would get back the accuracy measured in RMSE (root mean squared error). Yearly progress prizes, and especially the grand prize, would be measured against a different test set.

There were hundreds of forum and blog posts and research publications detailing the different approaches to the Netflix Prize. The first year progress prize was won by the Korbell team (Yehuda Koren, Robert Bell, and Chris Volinsky from AT&T labs) using an ensemble of a variation of SVD (singular value decomposition, although the variation is really more a matrix factorization than a traditional SVD) and RBM (restricted Boltzmann machines, a form of ANN). The SVD had an RMSE of 0.8914, the RBM 0.8990, and a linear blend of both got to an RMSE of 0.88.

It took 3 more years and thousands of teams trying to get from there to the 0.8572 RMSE on the test set that was required to win the grand prize. The winning entry was an ensemble of 104 individual predictors developed by multiple teams, and ensembled by a single layer neural network.

Making history

Back in 2006 there was no Kaggle, open source was something that fringe Linux hackers did on their “free time”, and AI was a dirty word. Taking that context into account, it is easy to see how groundbreaking the prize was in many ways. Releasing a large dataset and offering $1M to anyone who was able to beat a metric was definitely a bold move, and one that not many understood back in the day. Hell, many even don’t understand it nowadays.

I am pretty sure that without the Netflix Prize we would not have data competitions as we have now. Or, at the very least, it would have taken much more for Kaggle to take off. I have to wonder if much of the rest of the open ecosystem around AI, which includes from datasets à la Imagenet, to open source frameworks like TensorFlow or Pytorch, would be here if it hadn’t been for the Netflix Prize. Yes, I know that there was open source and even open data back in the day, but none of that was supported by a large company, let alone one that was actively supported with actual cash.

The grand Netflix Prize solution

The 2007 Progress Prize solution that combined SVD+RBM was already significantly better than the existing Cinematch algorithm. So, Netflix put a few engineers to work on productionizing the algorithm. That included rewriting the code and making it scalable, plus able to retrain incrementally as new ratings came in. When I joined Netflix I took over the small team that was working and maintaining the rating prediction algorithm that included the first year Progress Prize solution.

But, what about the grand Prize solution with the 104 algorithms? As I mentioned in a blog post back then, we decided it was not even worth to productionize. It would have taken a large engineering effort for a small gain in accuracy that was most likely not worth it for several reasons. The main one is that at that point in time, once the transition to streaming (vs DVD-by-mail) was obvious, it was clear that predicting consumption was much more important and impactful than predicting ratings.

Let’s talk ROI

I am often surprised that after reading the story above many will conclude that Netflix’ $1M investment was not worth it. That is definitely a very short-sighted read. Do you know how many Silicon Valley engineers Netflix can hire for 3 years for $1M? Probably less than one.

What did Netflix get from the $1M invested in the prize?

- Thousands of researchers and engineers around the world thinking about a problem that was important to Netflix

- A solution (the first year Progress Prize) that could be launched into production with measurable gains

- Becoming a recognizable brand name as a company that innovates in the space

One thing that I am absolutely certain of is that if it hadn’t been for the Netflix Prize me and many others like me would not have ended up working at Netflix. I doubt Netflix would have been able to innovate at the pace they did during those years if it wasn’t because of the talent that it attracted as a result of the prize. That in itself is worth much more than $1M.

Conclusion: are open algorithmic contests useful and valuable?

Of course, you can argue that I am quite biased on this topic. However, even as of today, I would say that there is huge value in them. Getting a large community to think about a data set and a particular problem often produces lots of insights and valuable results, some of which are applicable in practice. They also provide a unique opportunity for people around the world to learn, get some exposure, and in many cases even find a dream job they would not have found otherwise.

That being said, I do agree that algorithmic contests are not the silver bullet that will solve your company’s algorithmic needs. They should not be considered a way to outsource problems to cheaper countries. And, of course, it is important for the organizations in charge of proposing the competitions to make sure there are good incentives and fair rules. But I feel companies like Kaggle (now Google) have done a really good job at setting up the right framework for this.

Finally, I will say that I am very intrigued and interested by Andrew Ng’s proposal to turn algorithmic contests around by keeping the algorithm fixed while having participants work on the data in his Data-centric AI Competition. I am sure we can learn quite a lot from having a large community getting an incentive to work on data rather than on the algorithm.