DALL-E 2: An old professor with a notebook in his hand talking to a futuristic looking robot. 4k. Professional photo. Photorealistic

DALL-E 2: An old professor with a notebook in his hand talking to a futuristic looking robot. 4k. Professional photo. Photorealistic

Six months ago I published my Prompt Engineering 101 post. That later turned into a pretty popular LinkedIn course that has been taken by over 20k people at this point. That post and course were thought out as a gentle introduction to the topic. If you are new to prompt engineering, please start there. Also, a lot has happened in the world of LLMs since then. So, now is a good time to complement the Prompt Engineering 101 with an up-to-date and a bit more advanced post. I’ll call it Prompt Engineering 201. I will start off by repeating a “classic” technique that was already covered in the “advanced section” of the original post, Chain of Thought, but will build up from there.

Before we get into those techniques, a few words on what is Prompt Engineering.

Prompt Design and Engineering

Prompt Design is the process of coming up with the optimal prompt given an LLM and a clearly stated goal. While prompts are “mostly” natural language, there is more to writing a good prompt than just telling the model what you want. Designing a good prompt requires a combination of:

- Understanding of the LLM: Some LLMs might respond differently to the same prompt and might even have keywords (e.g. “endofpromt”) that will be interpreted in a particular way

- Domain knowledge: Writing a prompt to e.g. infer a medical diagnosis, requires medical knowlede.

- Iterative approach with some way to measure quality: Coming up with the ideal prompt is usually a trial and error process. It is key to have a way to measure the output better than a simple “it looks good”, particularly if the prompt is meant to be used at scale.

Prompt Engineering is prompt design plus a few other important processes:

- Design of prompts at scale: This usually involves design of meta prompts (prompts that generate prompts) and prompt templates (parameterized prompts that can be instantiated at run-time)

- Tool design and integration: Prompts can include results from external tools that need to be integrated.

- Workflow, planning, and prompt management: An LLM application (e.g. chatbot) requires managing prompt libraries, planning, choosing prompts, tools….

- Approach to evaluate and QA prompts: This will include definition of metrics and process to evaluate both automatically as well as with humans in the loop.

- Prompt optimization: Cost and latency depend on model choice and prompt (token length).

Many of the approaches herein can be considered approaches to “automatic prompt design” in that they describe ways to automate the design of prompts at scale. In the bonus section you will find some of the most interesting prompt engineering tools and frameworks that implement these techniques. However, it is important to note that none of these approaches will get you to the results of an experienced prompt engineer. An experienced prompt engineer will understand and be aware of all of the following techniques and apply some of the patterns wherever they apply rather than blindly following a particular approach for everything. This, for now, still requires judgement and experience. This is good news for you reading this. You can learn and understand these patterns, but you won’t be replaced by any of these libraries. Take these patterns as a starting tools to add to your toolkit, but also experiment and combine them to gain experience and judgement.

Advanced techniques

Here are the techniques I will be covering:

- Chain of thought (CoT)

- Automatic Chain of thought (Auto CoT)

- The format trick

- Tools, Connectors, and Skills

- Automatic multi-step reasoning and tool-use (ART)

- Self-consistency

- Tree of thought (ToT)

- Reasoning without observation (ReWoo)

- Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)

- Forward-looking active retrieval augmented generation (FLARE)

- Reflection

- Dialog-Enabled Resolving Agents (DERA)

- Expert Prompting

- Chains

- Agents

- Reason and Act (React)

- Rails

- Automatic Prompt Engineering (APE)

- Guidance and Constrained Prompting

Chain of Thought (CoT)

As mentioned, this technique was already discussed in the previous post. However, it is very noteworthy and it is at the core of many of the newer approaches, so I thought it was worthwhile to include here again.

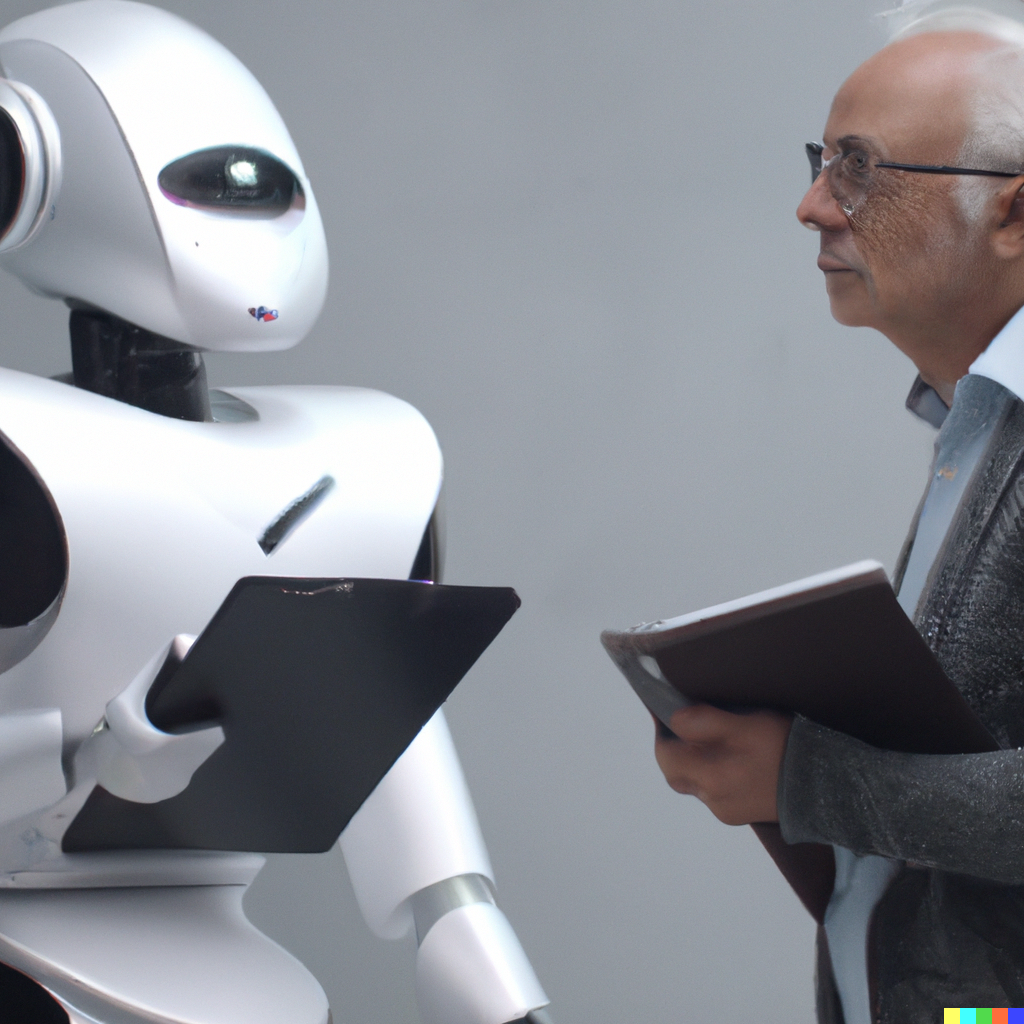

Chain of thought was initially described in the “Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models” paper by Google researchers. The simple idea here is that given that LLMs have been trained to predict tokens and not explicitly reason, you can get them closer to reasoning if you specify those required reasoning steps. Here is a simple example from the original paper:

Note that in this case the “required reasoning steps” are given in the example in blue. This is the so-called “Manual CoT”. There are two ways of doing chain of thought prompting (see below). In the basic one, called zero-shot CoT, you simply ask the LLM to “think step by step”. In the more complex version, called “manual CoT” you have to give the LLM examples of thinking step by step to illustrate how to reason. Manual prompting is more effective, but harder to scale and maintain.

Automatic Chain of Thought (Auto-CoT)

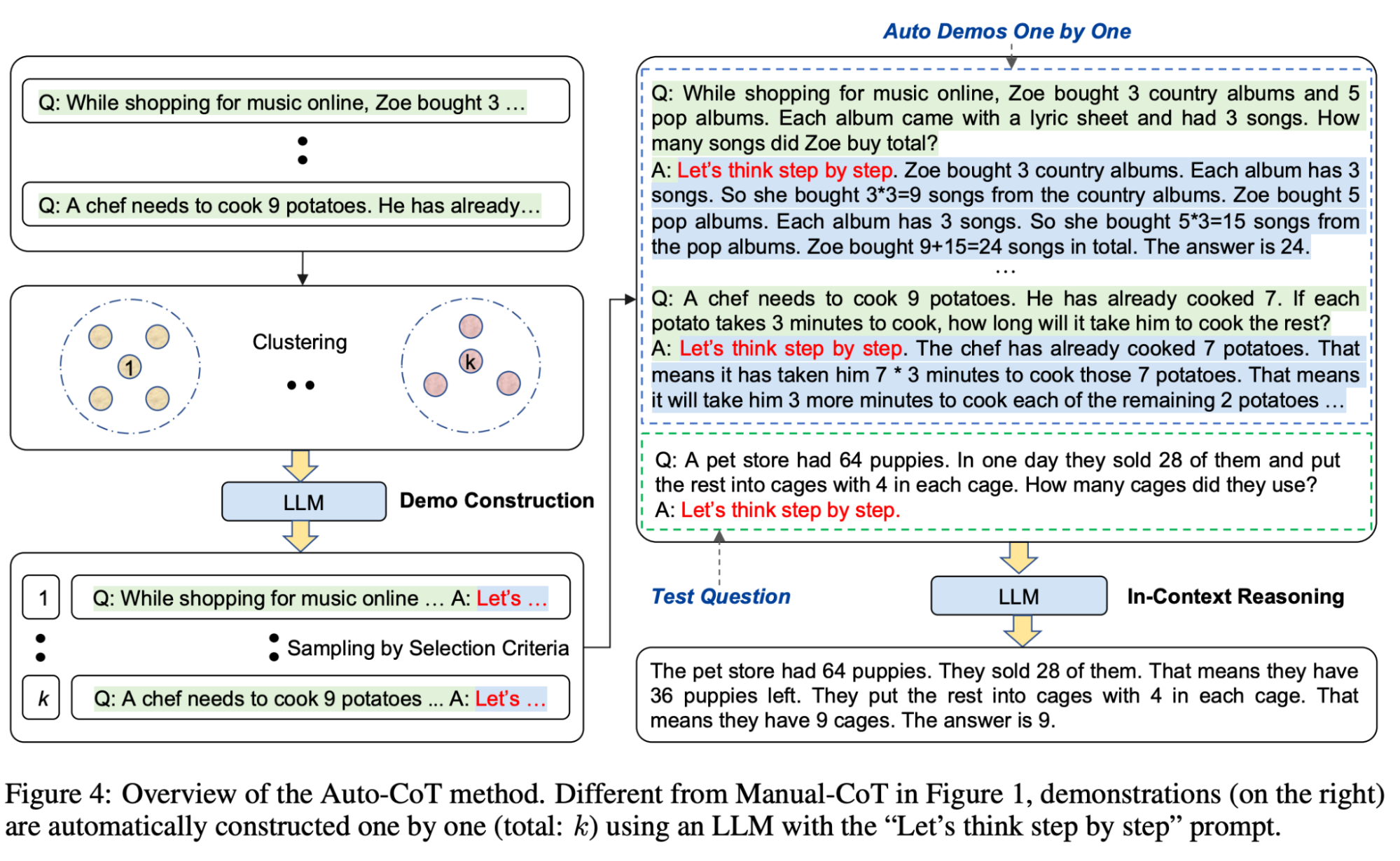

As mentioned above, manual CoT is more effective than zero-shot. However, the effectiveness of this example-based CoT depends on the choice of diverse examples, and constructing prompts with such examples of step by step reasoning by hand is hard and error prone. That is where automatic CoT, presented in the paper “Automatic Chain of Thought Prompting in Large Language Models”, comes into play.

The approach is illustrated in the following diagram:

You can read more details in the paper, but if you prefer to jump right into the action, code for auto-cot is available here.

The “format trick”

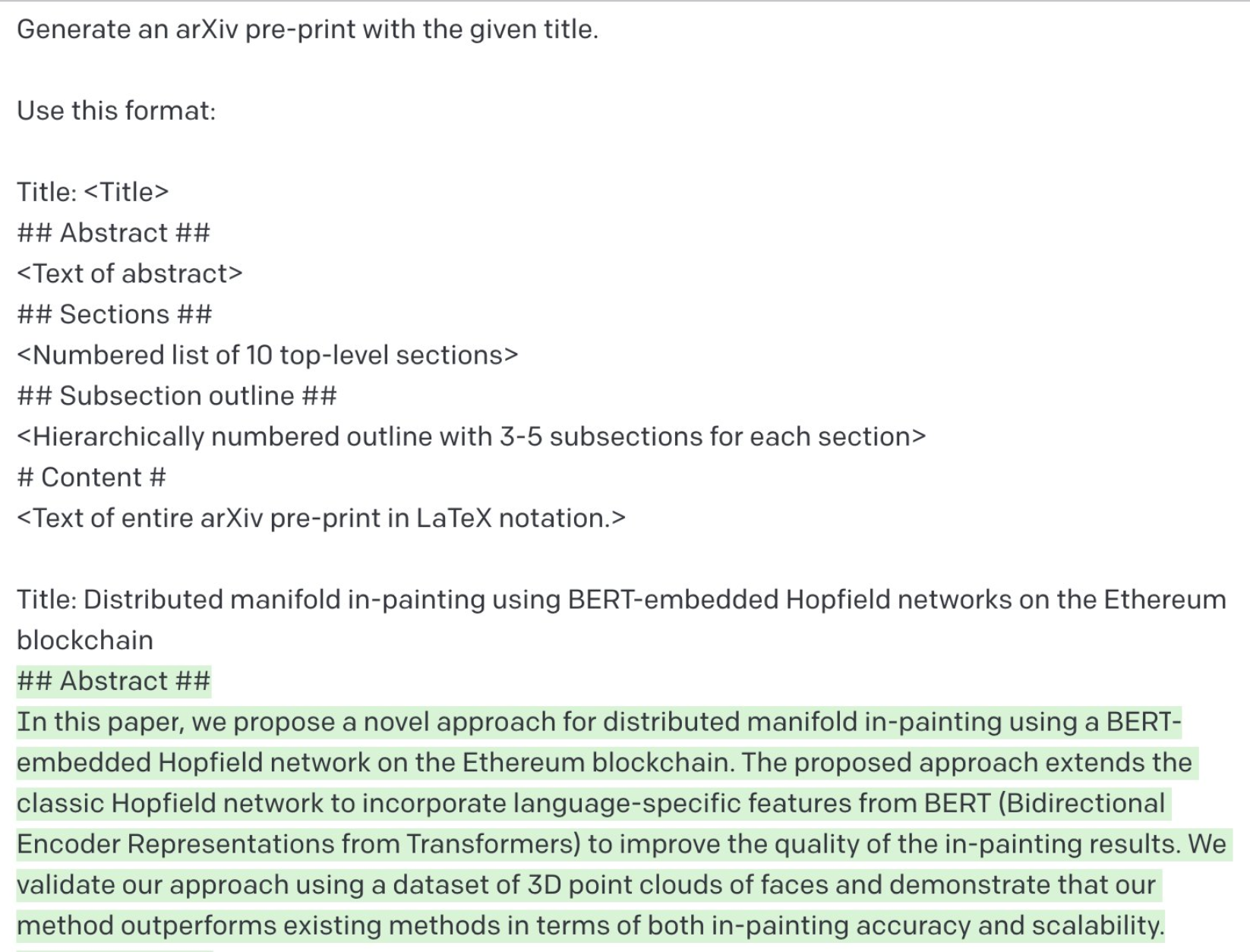

LLMs are really good at producing an output in a specific format. I don’t know if the “format trick” is a common term, but I did hear Riley Goodside use it in one of his presentations, so that is good enough for me. You can use the format trick for practically anything. Riley illustrated it by producing a LateX preprint for ArXiv.

However, if you specify code as the output format in your prompts you can do even more surprising things like generating a complete powerpoint presentation in Visual Basic.

Tools, Connectors, and Skills

Tools are generally defined as functions that LLMs can use to interact with the external world.

For example, in the following code from Langchain, a “Google tool” is instantiated and used to search the web:

Tools are also known as “Connectors” in Semantic Kernel. For example, here is the Bing Connector. Note that Semantic Kernel has a related concept of “Skill”. A skill is simply a function that encapsulates a functionality called by an LLM (e.g. summarize a text) but does not necessarily require a Connector or a Tool to access the external world. Skills are also sometimes called “affordances” in other contexts.

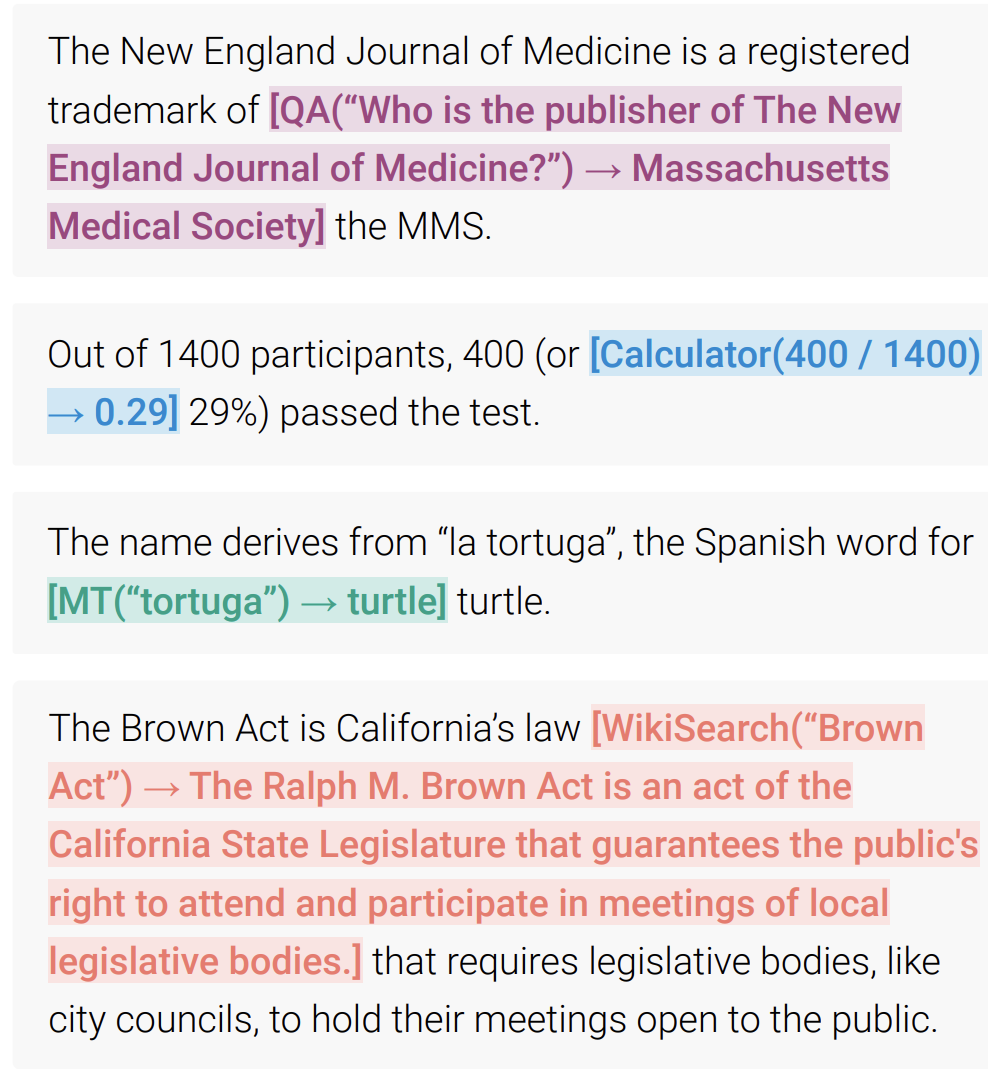

In the paper “Toolformer: Language Models Can Teach Themselves to Use Tools”, the authors go beyond simple tool usage by training an LLM to decide what tool to use when, and even what parameters the API needs. Tools include two different search engines, or a calculator. In the following examples, the LLM decides to call an external Q&A tool, a calculator, and a Wikipedia Search Engine.

More recently, researchers at Berkeley have trained a new LLM called Gorilla that beats GPT-4 at the use of APIs, a specific but quite general tool.

Automatic multi-step reasoning and tool-use (ART)

ART combines automatic chain of thought prompting and tool usage, so it can be seen as a combination of everything we have seen so far. The following figure from the paper illustrates the overall approach:

Given a task and an input, the system first retrieves “similar tasks” from a task library. Those tasks are added as examples to the prompt. Note that tasks in the library are written using a specific format (or parsing expression grammar to be more precise). Given those task examples, the LLM will decide how to execute the current task including the need to call external tools.

At generation time, the ART system parses the output of the LLM until a tool is called, at which point the tool is called and integrated into the output. The human feedback step is optional and is used to improve the tool library itself.

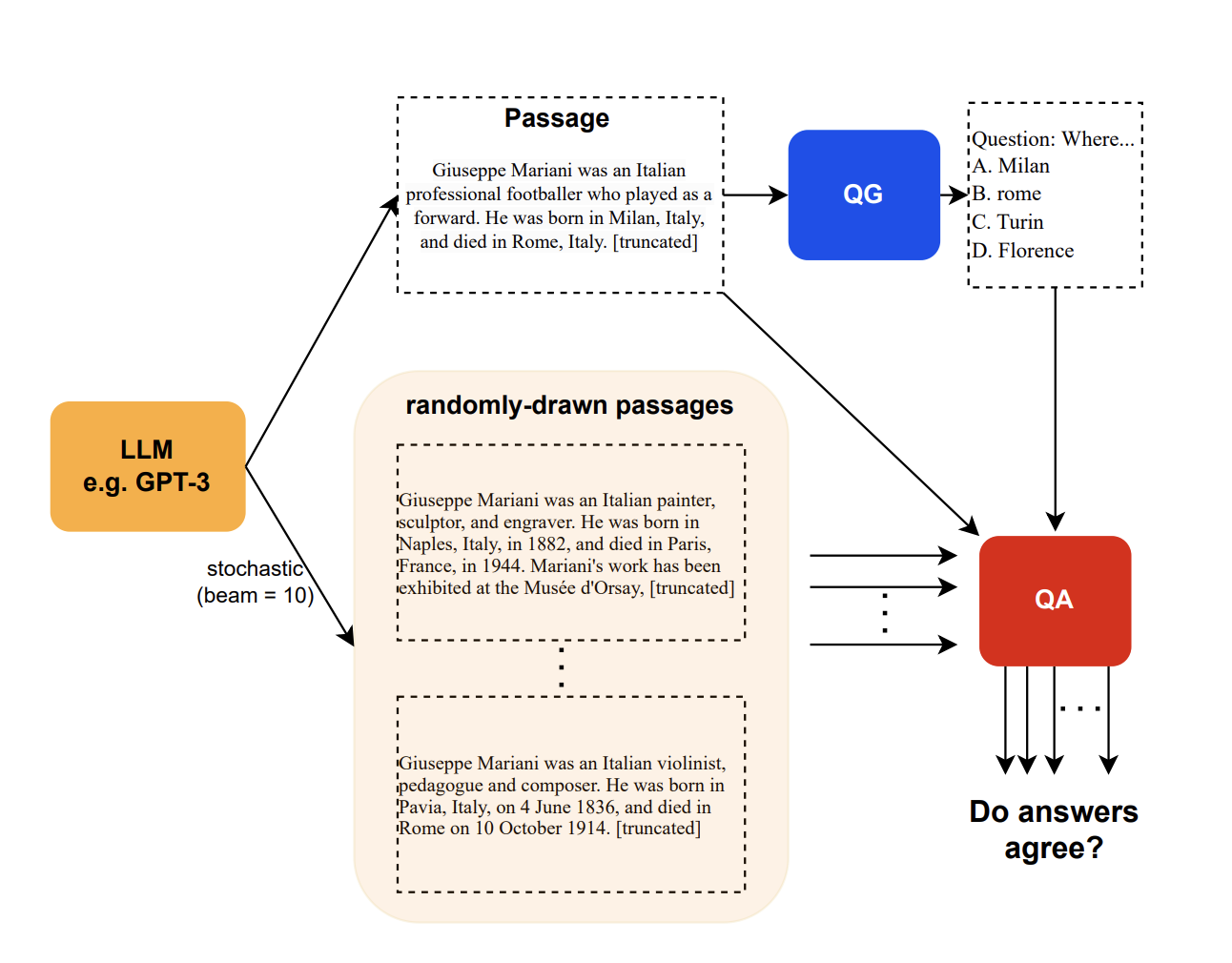

Self-consistency

Self consistency, introduced in the paper “SelfCheckGPT: Zero-Resource Black-Box Hallucination Detection for Generative Large Language Models”, is a method to use an LLM to fact-check itself. The idea is a simple ensemble-based approach where the LLM is asked to generate several responses to the same prompt. The consistency between those responses indicates how accurate the response may be.

The diagram above illustrates the approach in a QA scenario. In this case, the “consistency” is measured by the number of answers to passages that agree with the overall answer. However, the authors introduce two other measures of consistency (BERT-scores, and n-gram), and a fourth one that combines the three.

Tree of Thought (ToT)

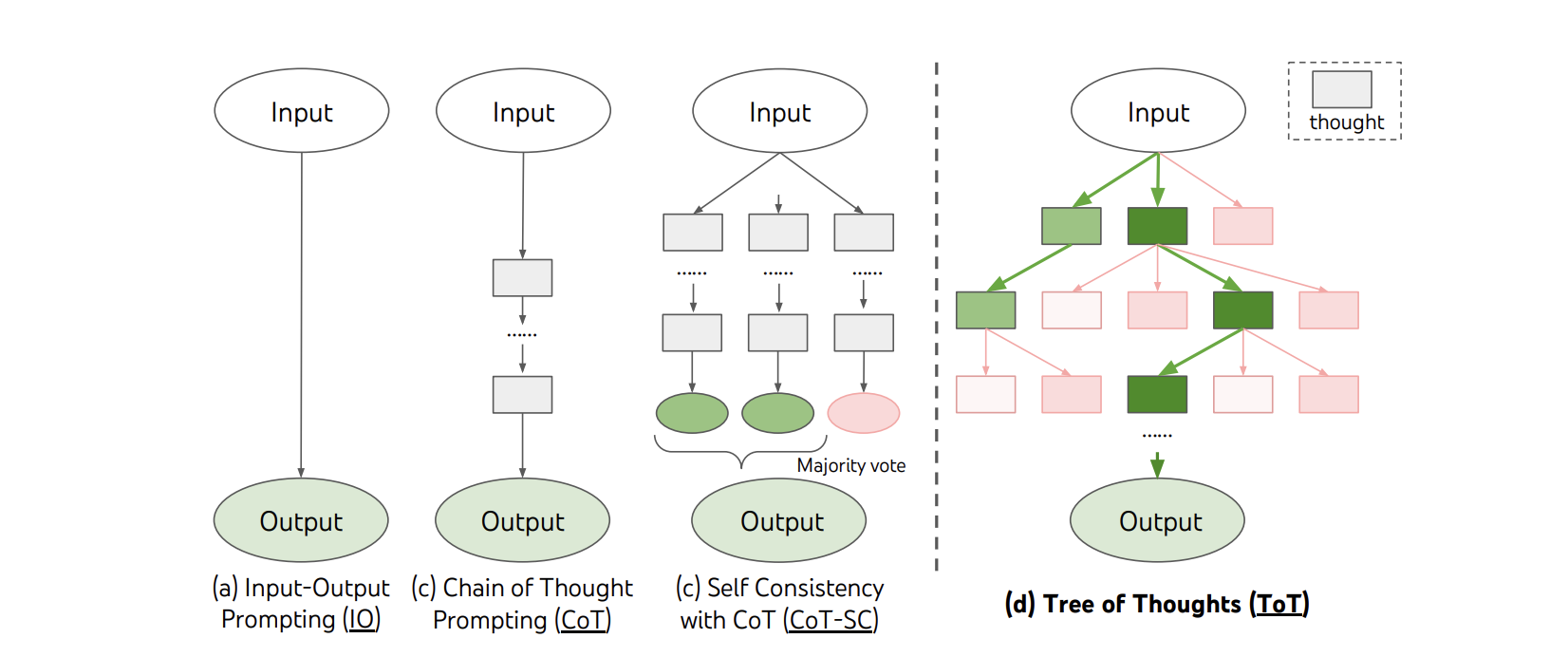

Trees of Thought are an evolution of the CoT idea where an LLM can consider multiple alternative “reasoning paths” (see diagram below)

ToT draws inspiration from the traditional AI work on planning to build a system in which the LLM can maintain several parallel “threads” that are evaluated for consistency during generation until one is determined to be the best one and is used as the output. This approach requires to define a strategy regarding the number of candidates as well as the number of steps/thoughts after which those candidates will be evaluated. For example, for a “creative writing” task, the authors use 2 steps and 5 candidates. But, for a “crossword puzzle” task, they keep up to a max of 10 steps and use BFS search.

Reasoning without observation (ReWOO)

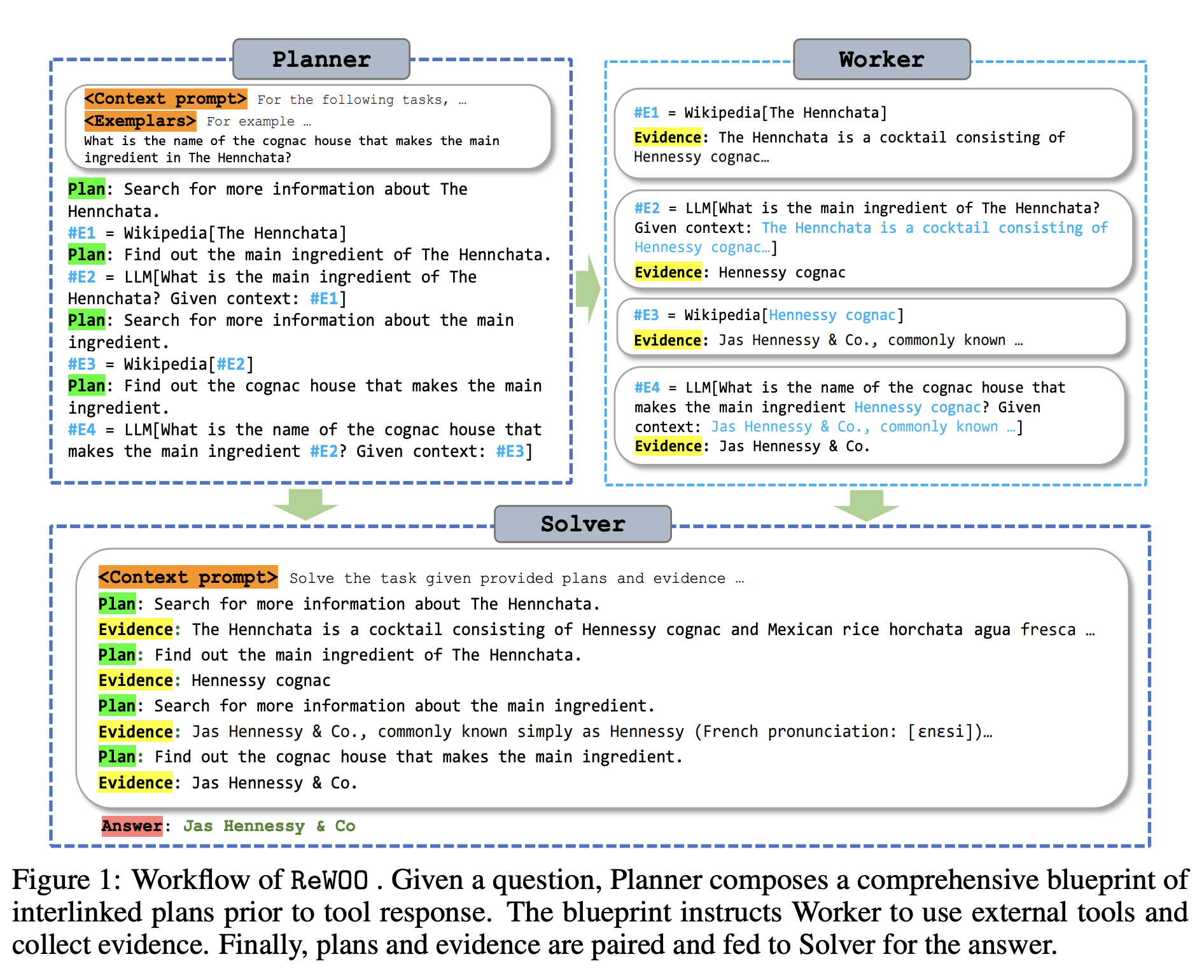

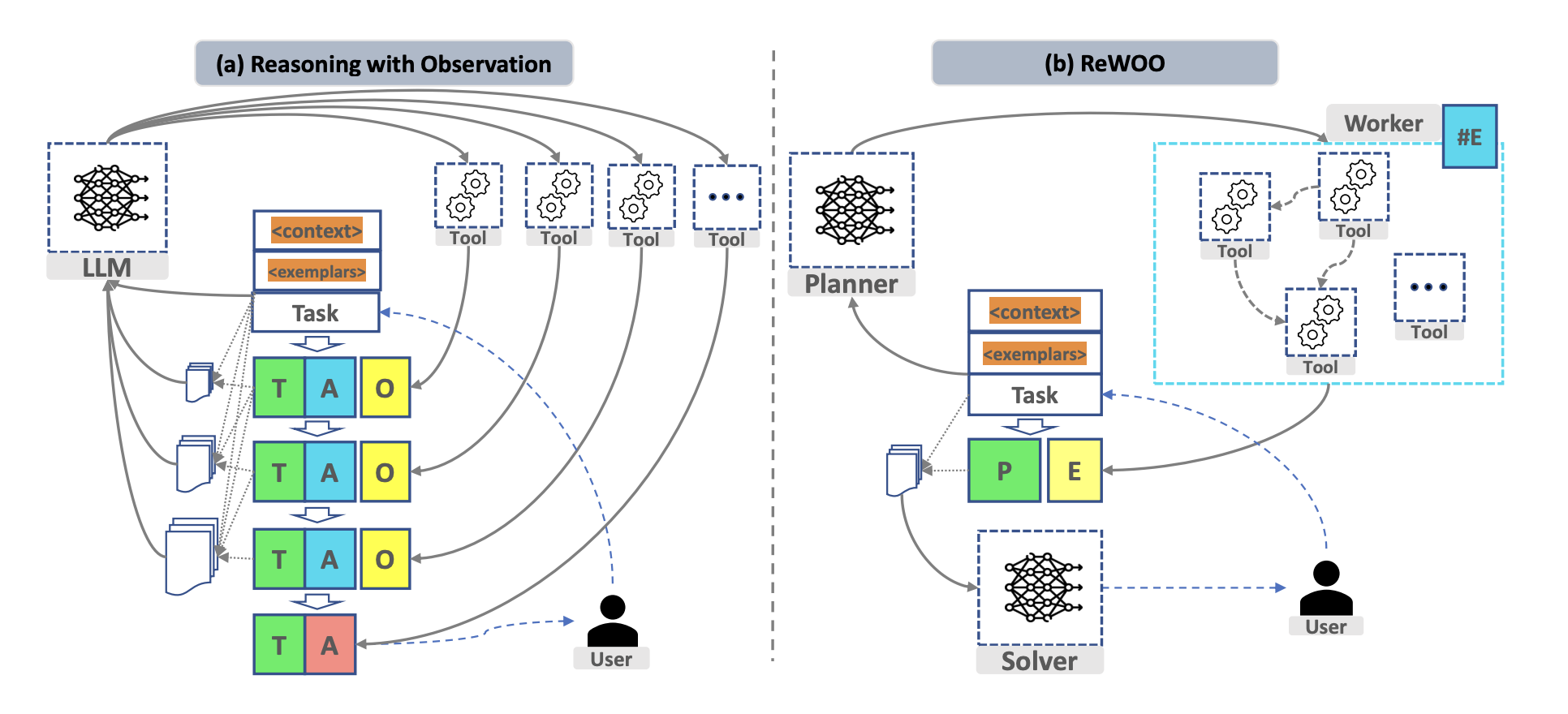

ReWOO was recently presented in the paper “ReWOO: Decoupling Reasoning from Observations for Efficient Augmented Language Models”. This approach addresses the challenge that many of the other augmentation approaches in this guide present by increasing the number of calls and tokens to the LLM and therefore increasing cost and latency. ReWOO not only improves token efficiency but also demonstrate robustness to tool failure, and also shows good results in using smaller models.

The approach is illustrated in the diagram below. Given a question, the Planner a comprehensive list of plans or meta-plan prior to tool response. This meta-plan instructs Worker to use external tools and collect evidence. Finally, plans and evidence are sent to Solver who composes the final answer.

The following image, also from the paper, illustrates the main benefit of the approach by comparing to the “standard” approach of reasoning with observations. In the latter, the LLM is queried for each call to a Tool (observation), which incurs in lots of potential redundancy (and therefore cost, and latency).

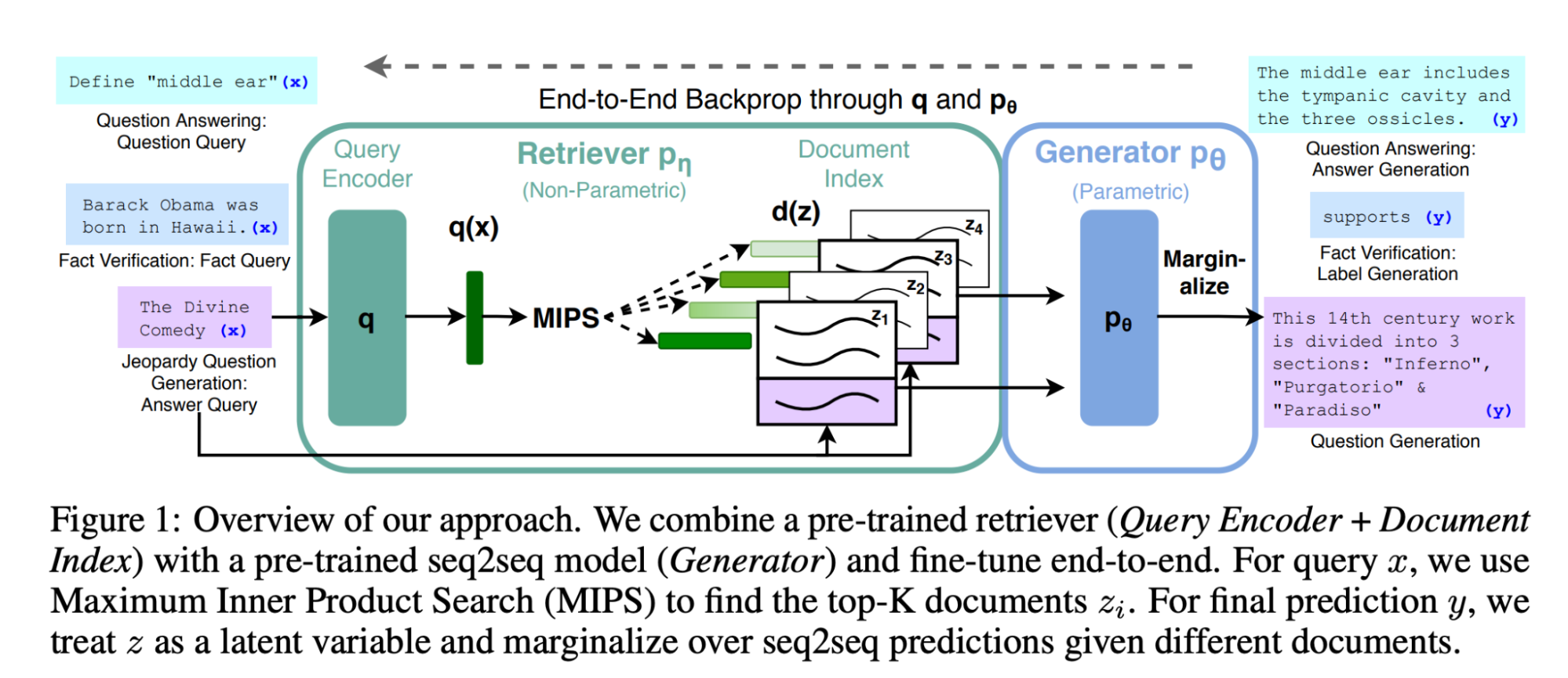

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)

RAG is a technique that has been used for some time to augment LLMs. It was presented by Facebook as a way to improve BART in 2020 and released as a component in the Huggingface library.

The idea is simple: combine a retrieval component with a generative one such that both sources complement each other (see diagram below from the paper.

RAG has become an essential component of the prompt engineer’s toolkit, and has evolved into much more complex approaches. In fact, you can consider RAG at this point almost as a concrete case of Tools, where the tool is a simple retriever or query engine.

The FastRAG library from Intel includes not only the basic but also more sophisticated RAG approaches like the ones described in other sections in this post.

Forward-looking active retrieval augmented generation (FLARE)

FLARE is an advanced RAG approach where, instead of retrieving information just once and then generating, the system iteratively uses a prediction of the upcoming sentence as a query to retrieve relevant documents to regenerate the sentence if it the confidence is low. The diagram below from the paper clearly illustrates the approach.

Note that the authors measure confidence by setting a probability threshold for each token of the generated sentence. However, other confidence measures might be possible.

Reflection

In the Self-consistency approach we saw how LLMs can be used to infer the confidence in a response. In that approach, confidence is measured as a by-product of how similar several responses to the same question are. Reflection goes a step further and tries to answer the question of whether (or how) we can ask an LLM directly about the confidence in its response. As Eric Jang puts it, there is “some preliminary evidence that GPT-4 possess some ability to edit own prior generations based on reasoning whether their output makes sense”.

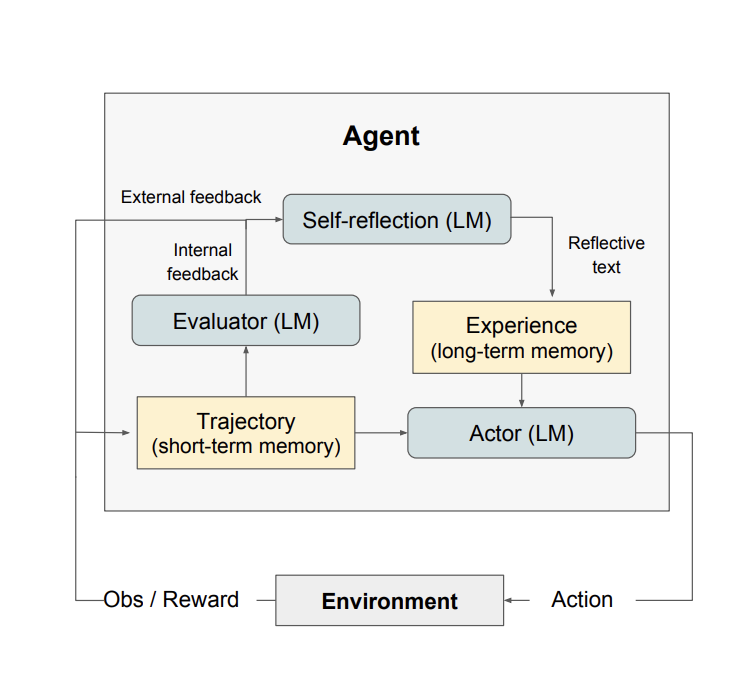

The Reflexion paper proposes an approach defined as “reinforcement via verbal reflection” with different components. The actor, an LLM itself, produces a trajectory (hypothesis). The evaluator produces a score on how good that hypothesis is. The self reflection component produces a summary that is stored in memory. The process is repeated iteratively until the Evaluator decides it has a “good enough” answer.

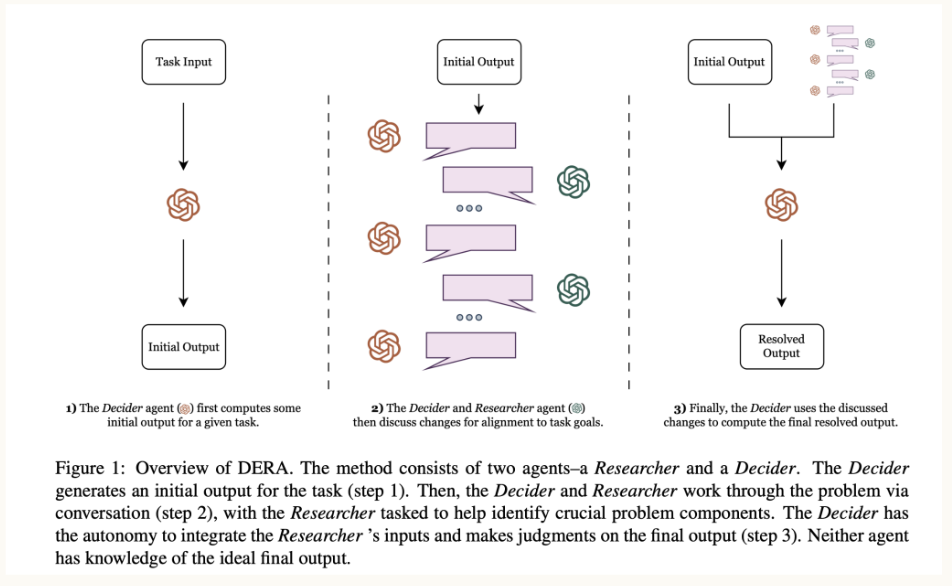

Dialog-Enabled Resolving Agents (DERA)

DERA, developed by my former team at Curai Health for their specific healthcare approach defines different agents that, in the context of a dialog take different roles. In the case of high stakes situations like a medical conversation, it pays off to define a set of “Researchers” and a “Decider”. The main difference here is that the Researchers operate in parallel vs. the Reflexion Actors that operate sequentially only if the Evaluator decides.

Expert Prompting

This recently presented prompting approach proposes to ask LLMs to respond as an expert. It involves 3 different steps:

- Ask LLM to identify experts in a given field related to the prompt/question

- Ask LLM to respond to the question as if it was each of the experts

- Make final decision as a collaboration between the generated responses

Introduced in the (controversial) “Exploring the MIT Mathematics and EECS Curriculum Using Large Language Models” beats other approaches like CoT or ToT. It can also be seen as an extension of the Reflection approach

Chains

According to LangChain, which I am going to consider the authoritative source for anything Chains, a Chain is “just an end-to-end wrapper around multiple individual components”

Now, of course, there are multiple types of Chains where you can combine different types and number of components in increasing complexity. In the simplest case, a chain only has a Prompt Template, a Model, and an Output Parser.

Very quickly though, Chains can become much more complex and involved. For example, the Map Reduce chain running an initial prompt on each chunk of data and then running a different prompt to combine all the initial outputs.

Since the process of constructing and maintaining chains can become quite an engineering task, there are a number of tools that have recently appeared to support it. The main one is the already mentioned LangChain. In “PromptChainer: Chaining Large Language Model Prompts through Visual Programming”, the authors not only describe the main challenges in designing chains, but also describe a visual tool to support those tasks. There is a tool with the exact same name and a similar approach available in Beta here. I am told this one has nothing to do with the authors of the original paper though. I haven’t used, so I can’t vouch for (or against) it.

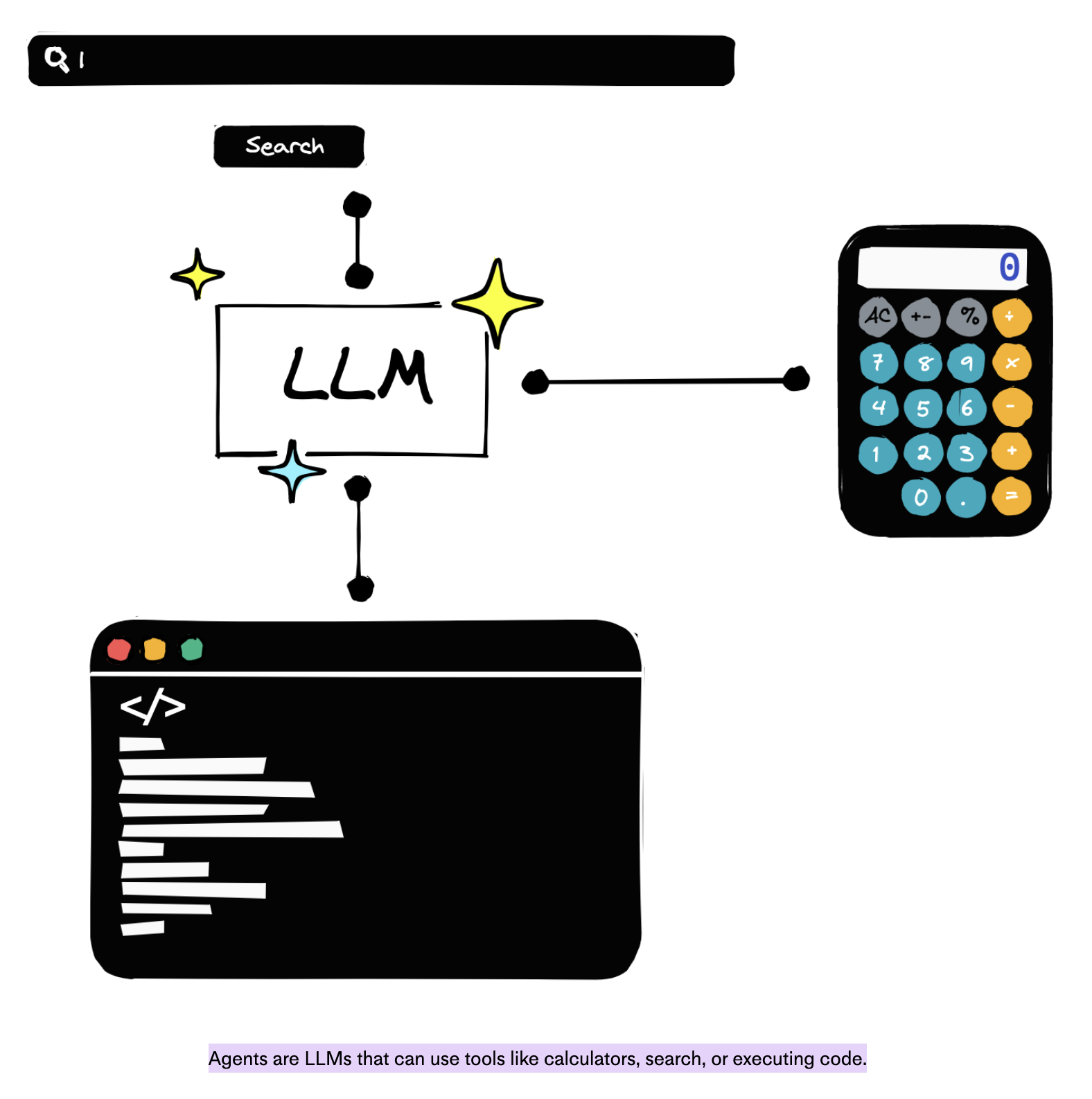

Agents

An agent is an LLM that has access to tools, knows how to use them, and can decide when to do so depending on the input (See here and here ).

Agents are not trivial to implement and maintain, that is why tools like Langchain have become a starting point for most people interested in building one. The “popular” Auto-GPT and also is just another toolkit to implement LLM agents.

Reason and act (React)

React is a specific approach to designing agents introduced by Google in “ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models”. This method prompts the LLM to generate both verbal reasoning traces and actions in an interleaved manner, which allows the model to perform dynamic reasoning. Importantly, the authors find that the React approach reduces hallucination from CoT. However, this increase in groundedness and trustworthiness, also comes at the cost of slightly reduced flexibility in reasoning steps (see the paper for more details).

As with chains and standard agents, designing and maintaining React agents is a pretty involved task, and it is worth using a tool that supports this task. Langchain is, again, the de facto standard for agent designs. Using Langchain, you can design different kinds of React agents such as the conversational agent, that adds conversational memory to the base (zero-shot) React agent (see here for examples and details).

Rails

A rail is simply a programmable way to control the output of an LLM. Rails are specified using Colang, a simple modeling language, and Canonical Forms, templates to standardize natural language sentences (see here )

Using rails, one can implement ways to have the LLM stick to a particular topic (Topical rail), minimize hallucination (Fact checking rail) or prevent jailbreaking (Jailbreaking rail).

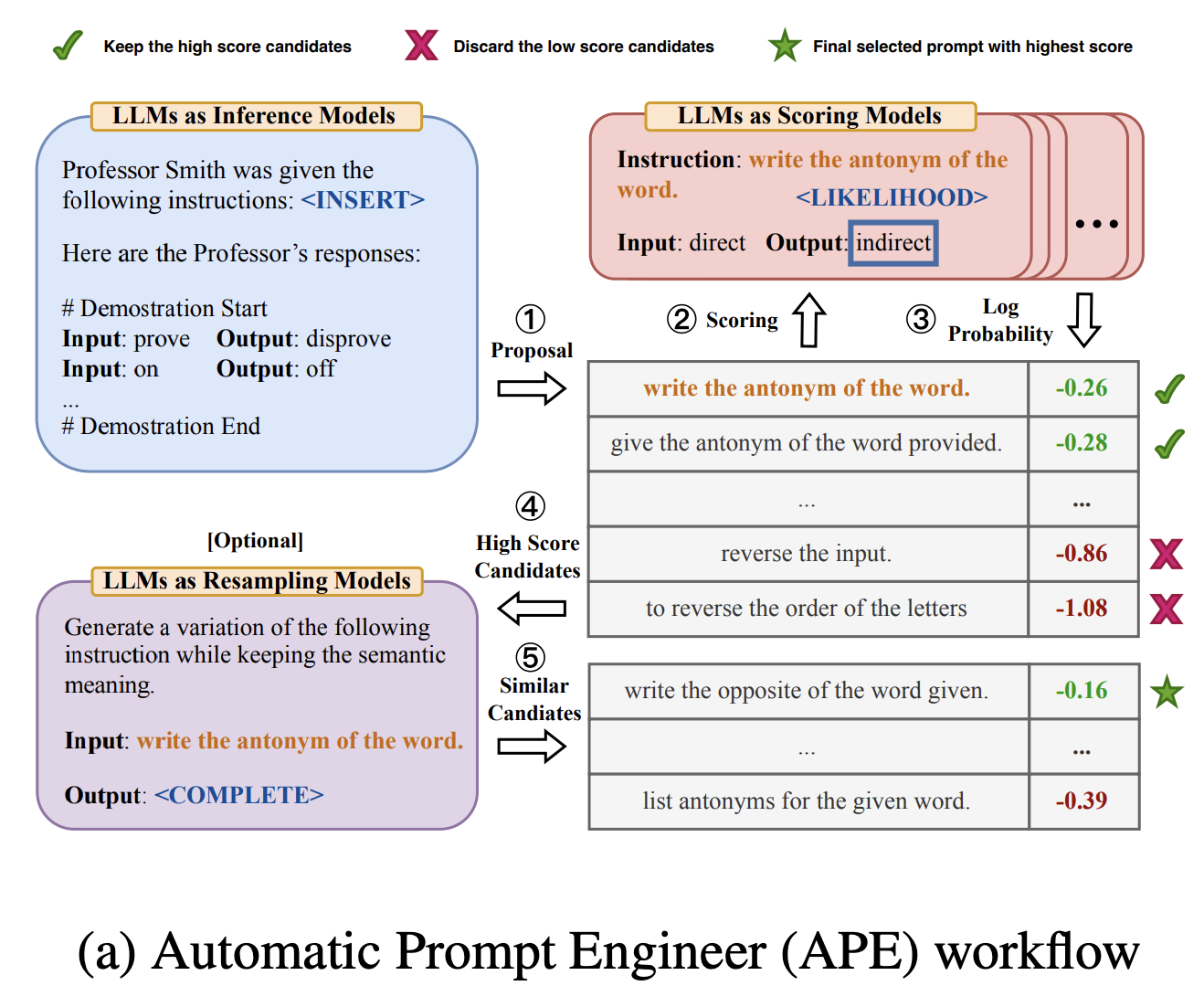

Automatic Prompt Engineering (APE)

APE refers to the approach in which prompts are automatically generated by LLMs rather than by humans. The method, introduced in the “Large Language Models Are Human-Level Prompt Engineers” paper, involves using the LLM in three ways: to generate proposed prompts, to score them, and to propose similar prompts to the ones scored highly (see diagram below).

Constrained Prompting

“Constrained Prompting” is a term recently introduced by Andrej Karpathy to describe approaches and languages that allow us to interleave generation, prompting, and logical control in an LLM flow.

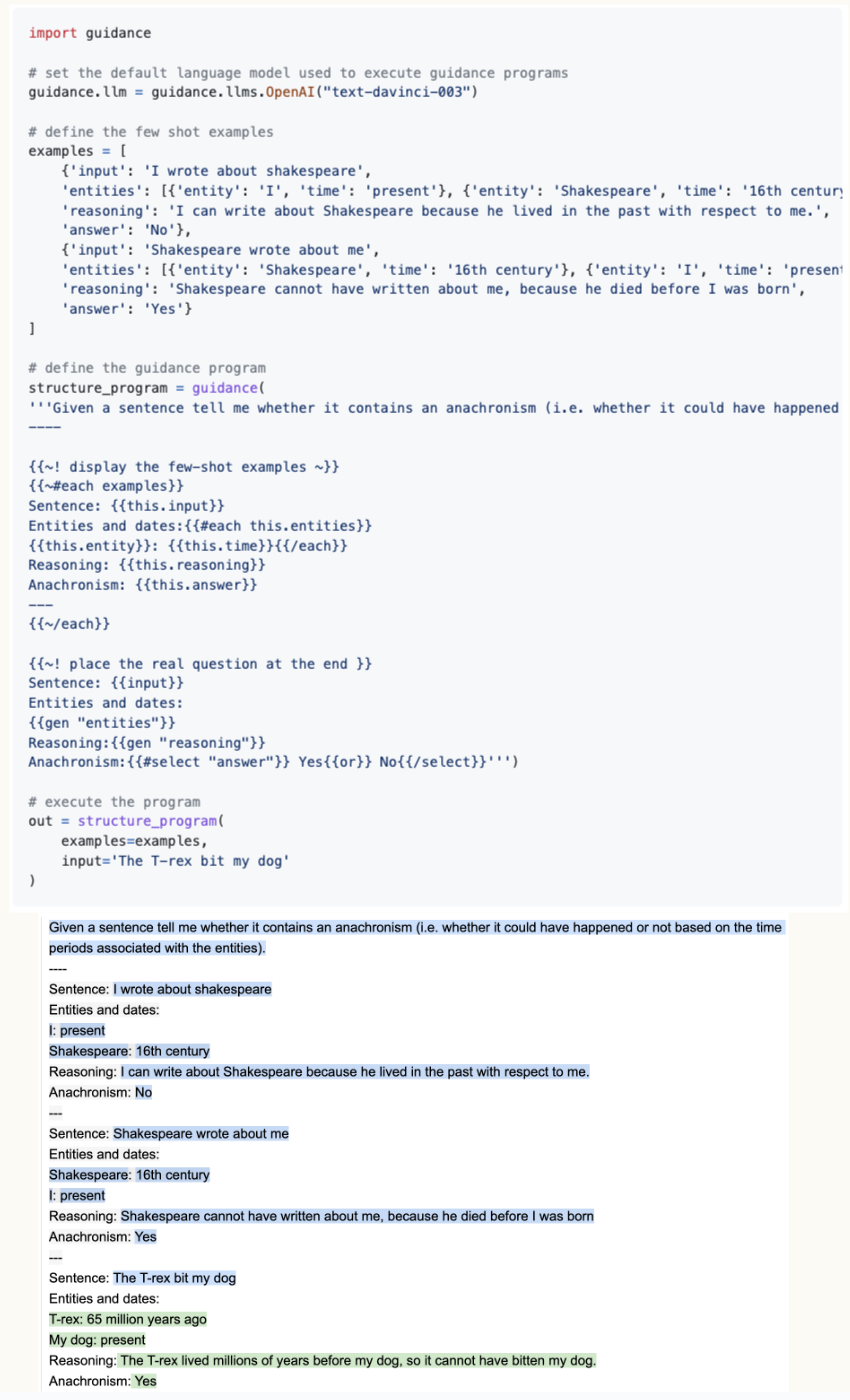

Guidance is the only example of such an approach that I know although one could argue that React is also a constrained prompting approach. The tool is not so much a prompting approach but rather a “prompting language”. Using guidance templates, you can pretty much implement most if not all the approaches in this post. Guidance uses a syntax based on Handlebars that allows to interleave prompting and generation, as well as manage logical control flow and variables. Because Guidance programs are declared in the exact linear order that they will be executed, the LLM can, at any point, be used to generate text or make logical decisions.

Prompt Engineering tools and frameworks

As we have seen throughout this guide, it is hard to implement

- Langchain

- Langchain is the most popular prompt engineering toolkit. While it initially mostly focused on supporting Chains, it now supports Agents and many different Tools for anything from handling memory to browsing.

- Semantic Kernel

- This toolkit developed by Microsoft in C# and Python is designed around the idea of skills and planning. That being said, at this point it also supports chaining, indexing and memory access and plugin development.

- Guidance

- Guidance is a more recent prompt engineering library also from Microsoft. Based on a templating language (see above) it supports many of the techniques in this post.

- Prompt Chainer

- Visual tool for prompt engineering

- Auto-GPT

- Popular tool for designing LLM agents

- Nemo Guardrails

- Recent tool by NVidia to build rails (see above) to make sure your LLM behaves as it should

- LlamaIndex

- Toolkit for managing the data that goes into an LLM application with mostly data connectors/tools.

- FastRAG

- From Intel, includes not only the basic RAG approach but also more sophisticated RAG approaches like the ones described in other sections in this post.